We all fall down, then get up again

Helpful lessons from the plague of 1665.

Sometimes history can take us out of ourselves and put the present in perspective.

It is hard not to be very worried about where Britain is headed as a country after arguably 20 years of catastrophic mistakes by a succession of administrations, including this one led by Boris Johnson.

But rather than dwell on that obvious and gloomy point, which I am sure most sensible people (and investors) are coming to share, let us swivel our gaze back 350 years to the parish records of London for inspiration.

There we can find data which demonstrates that terrible things pass, life changes and an orderly democratic society is usually self-correcting.

Thomas Cromwell, that effective man of business for Henry VIII, introduced compulsory birth, deaths and marriage registers for every parish in 1538. Lord Burleigh tightened the rules in 1597, appointing Diocesan registrars to inspect the accuracy of the books, and in 1653 in an Act Touching Marriages and the Registering thereof; and also touching Births and Burials, Oliver Cromwell put the system on a statutory footing, overseen by Magistrates.

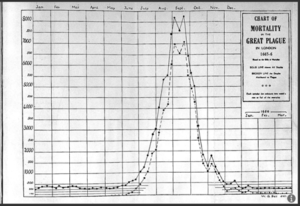

From this accurate data (reproduced by the Wellcome Trust), here is what we learn of the progress of the Plague of 1665-6. It began in May, it peaked over the summer, there was a second (but much lower) peak, but by the following February it was deemed safe enough for the court to return to Westminster.

The progress of the disease is gruesomely narrated by Samuel Pepys, in his diary. Interestingly, periwigs were deemed to be a source of transmission and wig manufacturers’ sales collapsed.

What are the lessons we are hesitantly to deduce from this evidence?

First, that even the most deadly viruses work their way through populations and at some point, everybody who is likely to get infected and, sadly, to die, will have done so.

Second, accurate detailed, local data – of which there was almost none at the press conference by the medical and scientific advisers this week (coincidentally timed to overshadow the online Labour conference) – is imperative to monitoring progress.

Third, orderly democratic law-making is a vital institutional underpinning of any successful society. That, currently, is suspended in Britain and needs to be restored.

Finally, the 1665 plague together with losses in a silly war with the Dutch, provided the backdrop to the fall of Charles II’s Lord Chancellor, the Earl of Clarendon. He did not get it himself but became seriously ill with gout and was deemed to be an increasingly incompetent liability. In 1667, he was impeached for breaching Habeus Corpus by sending prisoners out of the country to Jersey without trial, in violation of long-established law. In his prime, Clarendon had been brilliant and helped orchestrate the Restoration, but by the end it was King Charles II himself who signed his banishment.